By Scott DeJong

The tidal wave of information that came crashing alongside COVID-19 has become known as the ‘infodemic’ (Mina, 2018; United Nations, 2020; Zarocostas, 2020). One of the many concerns connected to the pandemic was the extensive sharing of conspiracy theories, misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation. Social media sites have tried to respond, with giants like Facebook attempting to combat the misinformation that is running rampant on their platforms (Jin, 2020). Others, like fact checking service snopes.com, have been tirelessly addressing misleading posts and articles that are coming across people’s screens (Echter, 2020).

Memes are no exception to these issues. Using templates that recontextualize images from popular culture, meme makers have exploited the meme format to propel narratives that might be misleading or downright incorrect (Castañeda Jr, 2020; Motta et al., 2020; Smith & Graham, 2019). While sometimes grouped together under the concept of fake news, researchers distinguish between misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation when considering non-factual information circulating online. According to Wardle and Derakshan (2016), “misinformation is information that is false, but the person who is disseminating it believes that it is true [while] disinformation is information that is false, and the person who is disseminating it knows it is false.” (p. 44). Finally, malinformation is, “information that is based on reality, but used to inflict harm on a person, organisation or country.” (ibid. p.44). Knowing the difference between these terms helps us understand how memes act within the infodemic space.

Mis-, dis-, and malinformed memes

In our sample, some pages adopted a sceptical, or even oppositional, stance to stay-at-home orders and the threat of COVID-19. The most common concerns that were embedded in these memes revolved around the economic impacts of the pandemic and government power. While these concerns might be valid, they are quickly coupled with unverified claims that question the validity of news reporting about the novel coronavirus and subsequently downplayed concern for COVID-19.

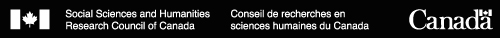

Memes with unsubstantiated rumors about the nature of a public health crisis run the risk of being exploited for detrimental claims about the appropriate medical response. Milner and Philips (2017) argue that memes encourage quick audience participation, which over time can expand and invite users to participate in a meme group. Over time, users can become more agreeable to the content that is shared in the groups they are part of. Other studies have furthered these claims, such as work by Smith and Graham (2019) which discusses how users in anti-vaccination groups engage in a variety of content across similar pages, making them more susceptible and agreeable to the proposed content. Critically, meme content is posted without citations or references provided to substantiate claims (see Figure 1). In this manner, memes can act as ways to engage the community on a page, where other content and material can further complement misleading memetic messages.

Our findings resonated with a recent study by Brennen et al. (2020) which found misinformation about the coronavirus circulating as “reconfigured content” where “true information is spun, twisted, recontextualized, or reworked” (Wardle 2019 as referenced in Brennen et al. 2020). They argue that reconfigured content has “higher engagement than content that was wholly fabricated” (Ibid.). Our current findings echo this claim. However, this creates a challenge in ascertaining if the memes creators are intentionally doing this (disinformation) or if they are spreading information they think is true (misinformation).

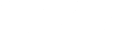

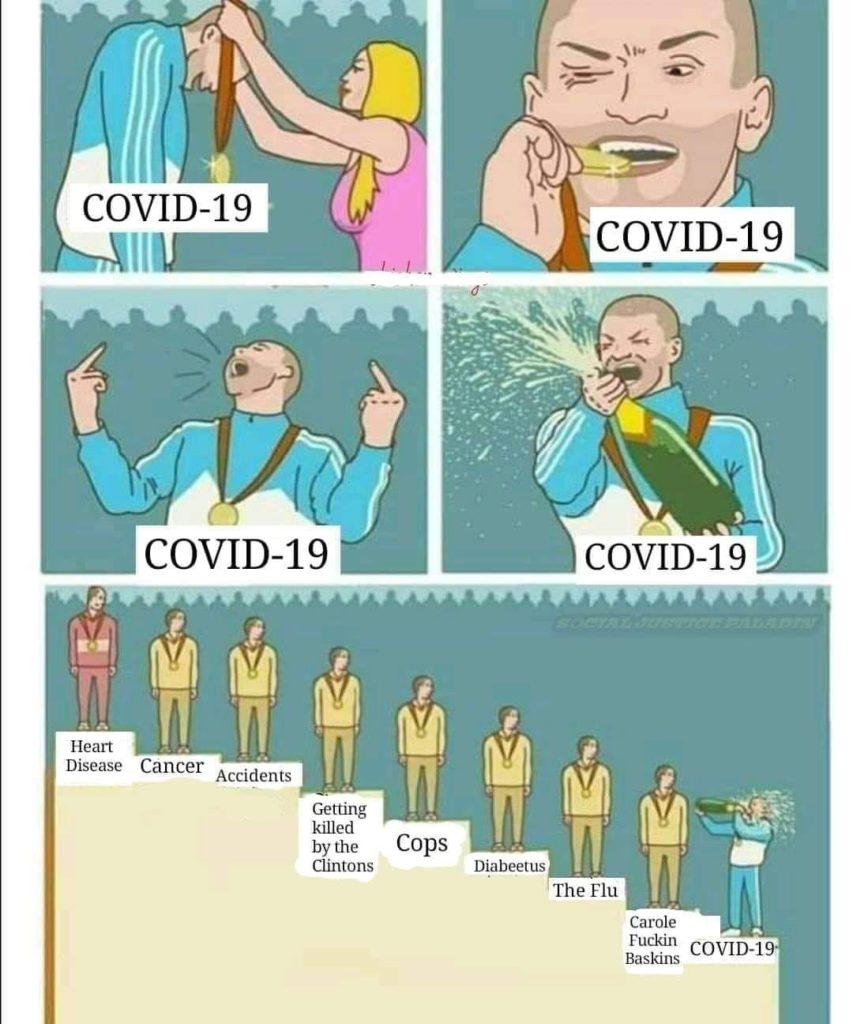

Memes, as Joan Donovan (2019) explains, have been taken up alongside propaganda initiatives where a “kernel of truth” makes it easier to pull off hoaxes through public sharing of content. For instance in Figure 1, while digital contact tracking by governments is a legitimate privacy concern, this image of Trudeau was posted on meme pages alongside text that implies a Liberal hidden agenda to surveil Canadian citizens while simultaneously undermining the legitimacy of the carbon tax. Figure 2 provides another example, placing the risk of COVID-19 on a pedestal below a mix of other legitimate health concerns and jokes from the hit show Tiger King. The meme presents true health issues in the form of a joke that attempts to dismiss the threat of the virus.

Generally, memes are being presented without sources, which makes their message hard to check for some users. Rather, the meme’s rhetoric becomes consistent with the meme page they were posted on. As Figure 1 and Figure 2 show in their discussion on surveillance or delegitimizing COVID-19, their goals are intentional. The page’s goals for posting content alongside twisted and reconfigured memes (Brennen et al., 2020), would classify these memes as disinformation sources. This finding matches with other scholars (Brennen et al.; Castañeda Jr, 2020) and reinforce the importance of following memes as communication mediums. While some of the anti-Trudeau pages that we track might also come close to malinformation by intentionally presenting incorrect statements about Trudeau, the majority of content we examined appears to be disinformation.

Conspiracy

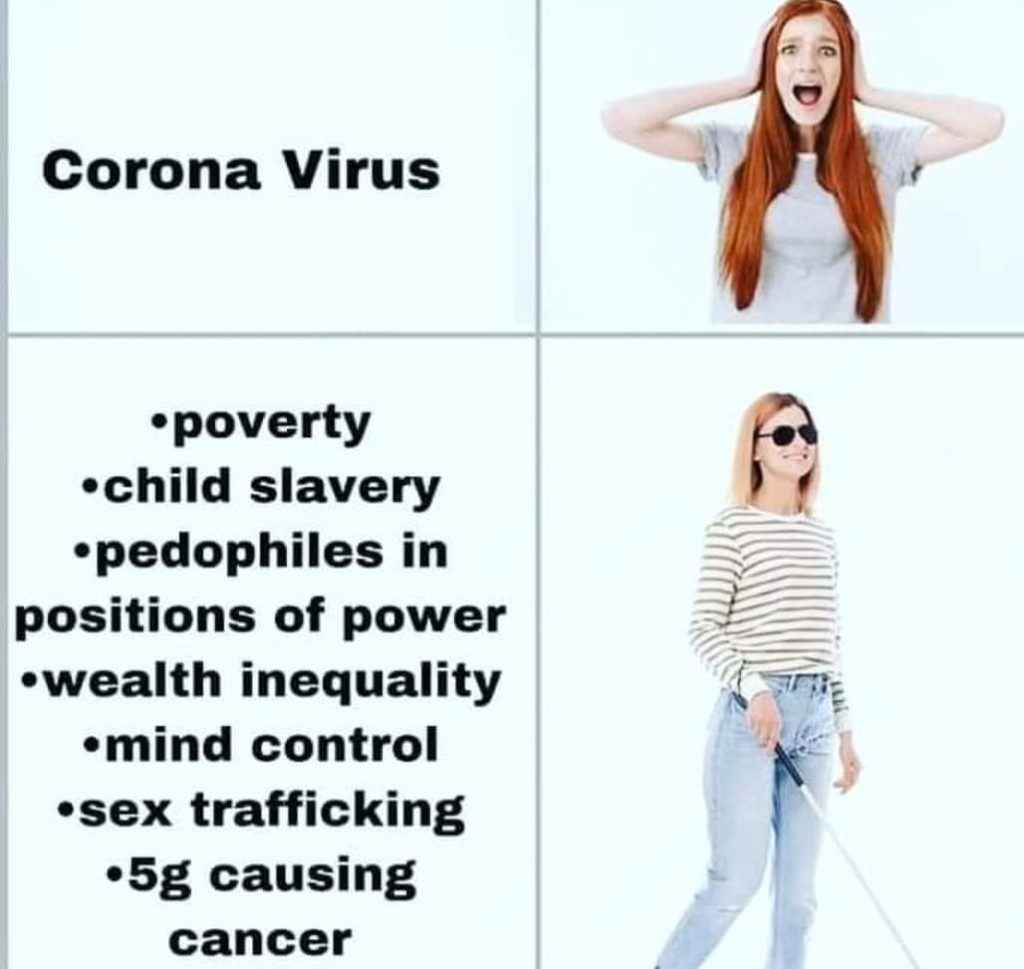

In some cases, disinformation expands into conspiracy, where issues of public concern are presented alongside conspiratorial claims. As exemplified by Figure 4, such memes casually further conspiracy theories around e.g. “mind control” and “5g causing cancer” by placing them alongside legitimate concerns about wealth inequality and poverty. According to a study from Reuters, this interplay of accurate and inaccurate information is commonplace as it obscures the difference between fact and fiction (Brennen et al., 2020).

We are finding evidence to support the claim made by Motta et al. (2020) that right-leaning groups have been more active in the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 than liberal or left-leaning ones. In our sample, we have found that statements which delegitimize news sources or push conspiracy narratives only appear on two of our tracked meme pages.

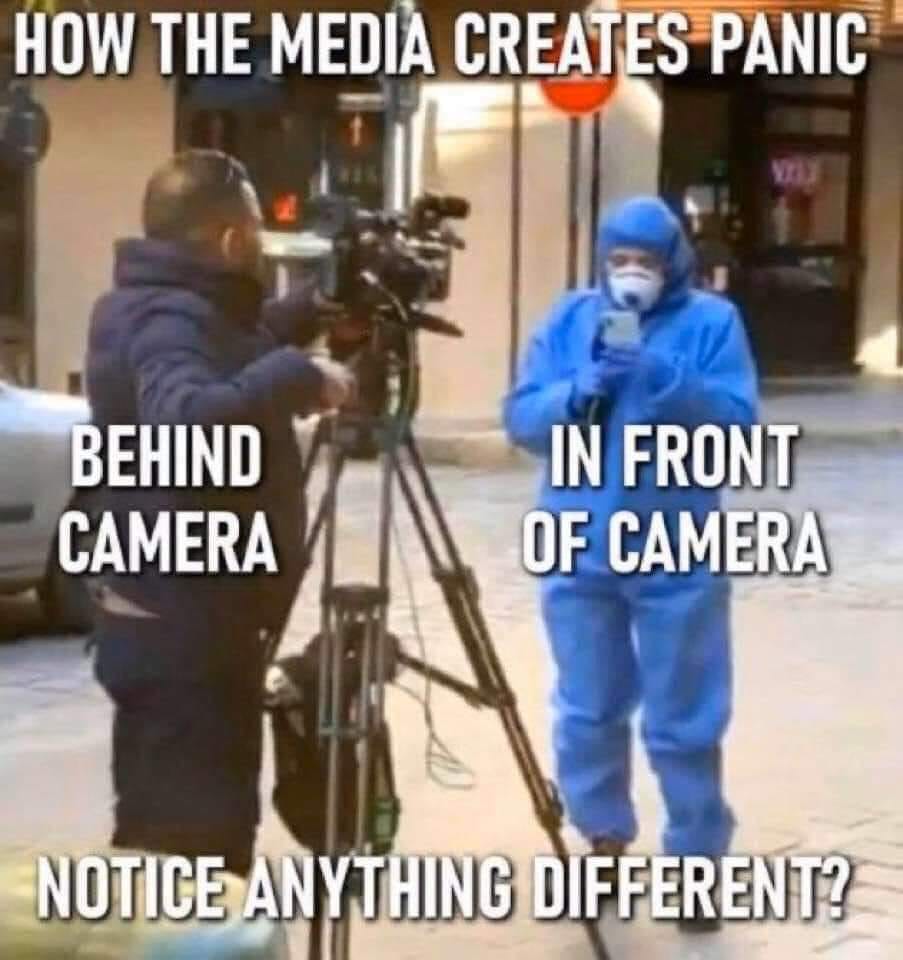

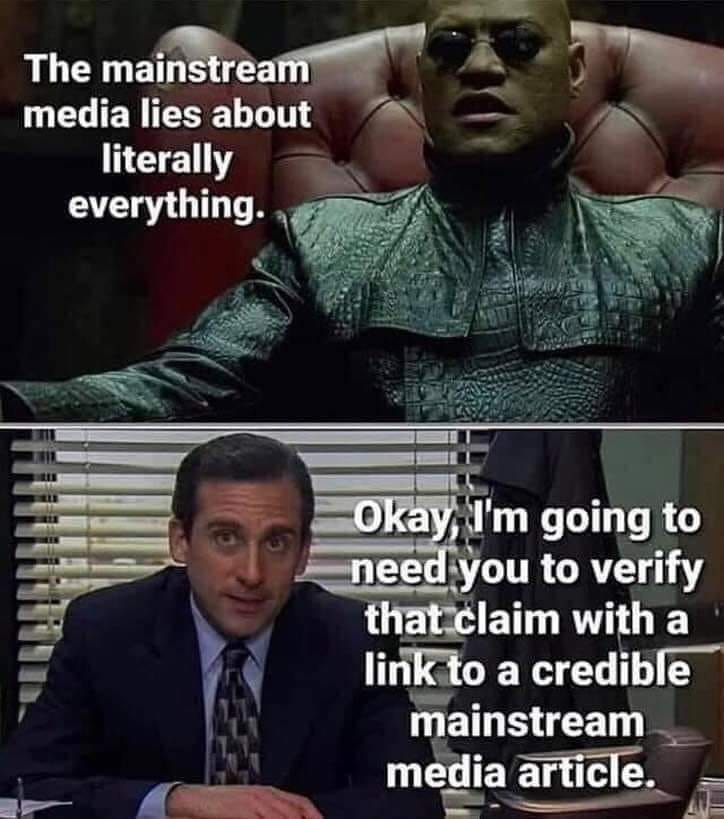

As the above memes show, these pages present a narrative that accuses the media of having ‘created’ the pandemic (Figures 3 and 5) and of overplaying the virus’ severity, therefore allegedly proving that they are unreliable sources of information. For instance, the upper panel of Figure 5 references a scene from “The Matrix” where individuals are offered a red or blue pill, a popular right-wing reference that has been recently picked up by pro-Bernier groups around making themselves “aware” of “mainstream media lies”. This is juxtaposed with a lower panel image of Michael Scott, the protagonist of television sitcom “The Office”, whose characteristic buffoonery is meant to support the meme’s overall message.

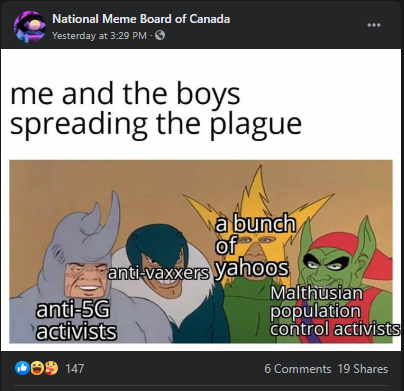

However, it is important to note that conspiracy is still discussed on pro-Liberal and pro-NDP pages. But instead of supporting them, the pages posted memes which mock the conspiracy theories that are circulating in right-wing memespace. During the middle of May, when discussion about the pandemic was at its highest, the pages shared memes which made fun of certain conspiracy groups (Figures 6 and 7). Many of their memes referred to so-called Malthusian theory about population growth and control.

Conclusion

Our preliminary findings suggest that creating and sharing memes is a communicative practice whereby pro-Bernier groups gradually integrate conspiracy theories about COVID-19 into their memetic repertoire. While these groups also shared text and screenshots of news articles with captions that aimed to support their claims, memes contained the majority of misinformation or conspiracy claims. This reminds us of the possibilities of visual arguments to create relationships and connections. As our current findings show, memes provide an approachable template for discussing ideas and presenting opinions, including conspiracy theories. The meme groups we are tracking have used this to spread misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy, especially discrediting Canadian news outlets in order to support alternative agendas. Meme’s generate conversation, which is picked up by other pages who react to popular ideas that are being discussed on meme groups across the Canadian political spectrum. This disparity in dialogue across meme groups, emphasizes the importance of following memetic conversations and the variety of opinion being taken up around different issues, whether it is true or false.

References

Brennen, S., Simon, F., Howard, P., & Nielson, R. (2020). Types, sources, and claims of COVID-19 misinformation. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Castañeda Jr, J. (2020). Memes of Misinformation: Federal Spending: Unraveling the controversial, socio-economic and political issues behind those annoying social media memes. Vernon Press.

Milner, R. M., & Phillips, W. (2017). The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Polity.

Mina, N. G., An Xiao. (2018, August 30). How Misinfodemics Spread Disease. The Atlantic.

Motta, M., Stecula, D., & Farhart, C. (2020). How Right-Leaning Media Coverage of COVID-19 Facilitated the Spread of Misinformation in the Early Stages of the Pandemic in the U.S. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000396

Smith, N., & Graham, T. (2019). Mapping the anti-vaccination movement on Facebook. Information, Communication & Society, 22(9), 1310–1327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1418406

United Nations. (2020). UN tackles ‘infodemic’ of misinformation and cybercrime in COVID-19 crisis. United Nations; United Nations.

Wardle, C. (2016, November 18). 6 types of misinformation circulated this election season. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/6_types_election_fake_news.php

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet, 395(10225), 676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X