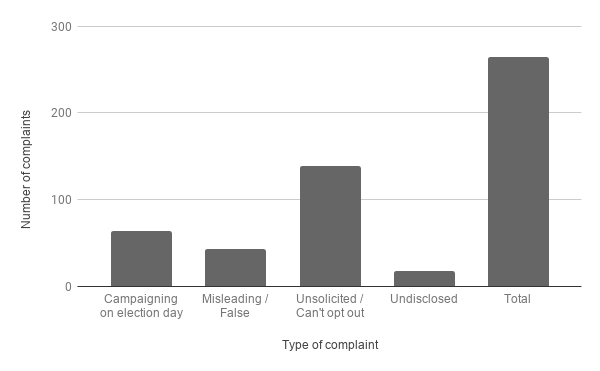

Key findings:

- 53% of analysed complaints by voters to Elections Canada in 2015 related to unsolicited contact by political parties without an opt-out possibility (139 out of a sample total of 264)

- Other types of complaints ranked much lower: campaigning on election day (24%), misleading or false information (16%), and undisclosed affiliation (7%)

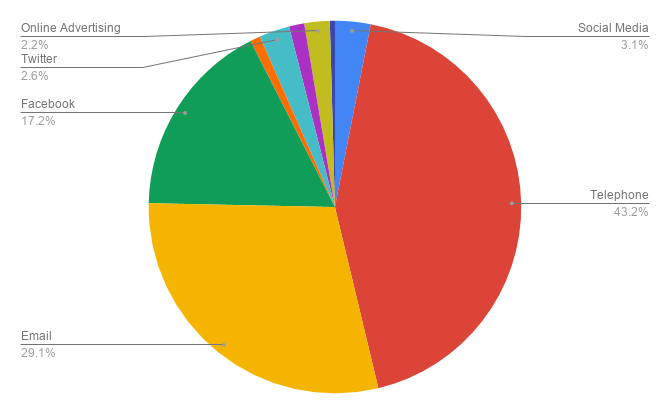

- The vast majority of targeted campaign activities that voters complained about happened over the phone (43%), via email (29%) or through Facebook (17%)

Analysis

Digital advertising is an everyday practice for businesses, NGOs and political parties alike. It promises to reach specific audiences—potential customers, supporters or voters—more effectively, with targeted messages. But we know little about whether Canadians like targeted ads, especially in politics. Our research team looked at complaints that Canadians had submitted to Elections Canada for the 2015 Federal Election to learn about public attitudes to digital advertising by parties during elections.

These results supplement the little survey data we have about Canadians’ attitudes to digital advertising. Almost a third of Canadians (29%) have an ad blocker installed according to the 2018 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, suggesting that many try to opt-out of digital advertising.

The reason may be because they worry about the privacy implications of digital advertising. 73% of respondents are concerned about potential privacy violations from using Facebook as reported by the 2019 Canada’s Internet Factbook. The same survey found that after learning that social media companies can store and share users’ personal information without their knowledge or consent, 43% of Canadians said they changed their privacy settings, while 32% took no action or reduced their use of social media.

Many Canadians are also confused about how online advertising works, as we also find. About a third of respondents think their mobile device listens to them via the microphone without their permission.

Complaints about targeting practices in Canadian Federal Elections

Via two Access to Information Requests, we obtained 598 pages of complaints related to online advertising. We coded a total of 264 complaints by platform while developing criteria for the nature of the complaint. Analysing the data revealed interesting findings about why voters turned to Elections Canada to complain, and which platforms used for targeted advertising elicited negative responses from voters.

Types of complaint

The vast majority of voters who complained to Elections Canada about campaign practices by political parties were concerned about the fact that the contact was unsolicited without giving them a possibility to opt out. In their perception, this was often compounded by the fact that they did not know how the party in question had obtained their contact information.

“This morning, I received an unsolicited email allegedly from [name of candidate] telling me the following: (…) I am very disturbed by this, primarily because at no time in my life, have I ever given my personal email address to [name of political party]. I have never voted for this party and have never supported them with email, other than when complaining to my MP. To me, this is unsolicited spam. Out of curiosity, I tested the links provided in the PS section, and in no case was I given the option to “UNSUBSCRIBE” from any further email. And so I am registering a complaint against [name of political party] for wasting my time and for invading my privacy.”

Complaint to Elections Canada, 2015

Many complainants were perturbed by the fact that political parties were still campaigning on election day. Often these complaints confused what was and was not election advertising—an indication that election advertising is not as clear cut in the minds of voters as it is before the law. In Figure 1, a voter complains about seeing a message posted on election day that seems like advertising. Elections Canada permits these posts on election day as they do not have a “placement cost” and thereby do not count as advertising.

A smaller number of voters were concerned about targeted advertisement that did not disclose party affiliation, especially where it concerned campaigning activities by third parties. Figure 2, for example, shows a third-party ad that appeared like a news story to one voter, suggesting ongoing confusion among voters about how to distinguish news from advertising online.

Platforms complained about

Phone calls, including both live and recorded ones (“robocalls”), were named by most complainants as the platform that political parties were using to get in touch with them. Emails make up the second big chunk of complaints, followed by Facebook.

Other social media channels, TV and Radio figured only marginally in the complaints. Many complainants want to know how political parties obtained their contact information, and enquire whether the targeting practice in question constitutes a violation of the law.

“Although I understand candidates have to campaign it is a bit annoying and very intrusive when your evening is disrupted by numerous robocalls from one candidate. Absolutely ridiculous. This method of campaigning has to change. I’m sure they would not appreciate it if I called with a recording to their home 3 or more times in one night.”

Complaint to Elections Canada, 2015

While we cannot assess Elections Canada’s overall response to these complaints, some complaints in our sample included a response from the independent institution clarifying the law to the complainant.

Ambiguous attitudes toward targeted advertisement and use of personal data

These election complaints support what we know from other studies: targeted advertising is unpopular. Two recent studies from the US have pointed to ambiguities in public attitudes toward micro-targeting in elections and customer surveillance. In their 2013 survey study, Eitan D. Hersh and Brian F. Schaffner conclude that voters on average in fact do not support candidates who reach out to them with specific messages based on their (assumed) group identity. Contrary to the rationale behind targeting, voters seem to prefer ambiguous messages based on broad, general principles – and tend to penalize candidates who target them by mistake, hence cancelling out the positive returns of successful targeting.

In the cases above, voters complained when they received ads from political parties they did not plan on voting for. We did not, however, see many complaints about the ads being too targeted, or knowing too much about voters.

On a more general level, Nora A. Draper and Joseph Turrow point out that many people would like to protect their privacy and limit companies’ (or, by extension, political parties’) use of their personal data, but often feel unable to do so. Obscure communication practices of corporations trying to protect their gains from consumer surveillance prevent individuals from making informed decisions about what happens to their data. This often means they don’t act at all, succumbing to “digital resignation” due to feelings of frustration, futility, and cynicism.

Complaints about not being able to opt-out or questioning how they ‘got added to the list’ suggests that many people feel out of control regarding their communication preferences in a digital age. That Elections Canada has little to help the voters address their concerns suggests that these complaints will do little to quell this public frustration.

Thanks to Thomas Hackbarth and Margaret MacDonald for coding election complaints. Janna Frenzel wrote this post with Dr. Fenwick McKelvey.